Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư

| Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư 大越史記全書 |

|

|---|---|

Cover of the "Nội các quan bản" version (1697) |

|

| Author(s) | Ngô Sĩ Liên (original edition) |

| Original title | 大越史記全書 |

| Country | Đại Việt |

| Language | Hán tự |

| Subject(s) | History of Vietnam |

| Genre(s) | Historiography |

| Publisher | Lê Dynasty |

| Publication date | 1479 (original edition) |

| Preceded by | Đại Việt sử ký |

| Followed by | Khâm định Việt sử Thông giám cương mục |

| Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư | |

|---|---|

| Vietnamese name | |

| Quốc ngữ | Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư |

| Chữ nôm | 大越史記全書 |

The Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư (大越史記全書; Complete Annals of Đại Việt) is the official historical text of the Lê Dynasty, that was originally compiled by the royal historian Ngô Sĩ Liên under the order of the Emperor Lê Thánh Tông and was finished in 1479. The 15-volume book covered the period from Hồng Bàng Dynasty to the coronation of Lê Thái Tổ, the first emperor of the Lê Dynasty in 1428. In compiling his work, Ngô Sĩ Liên based on two principal historical sources which were Đại Việt sử ký by Lê Văn Hưu and Đại Việt sử ký tục biên by Phan Phu Tiên. After its publication, Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư was continually supplemented by other historians of the Lê Dynasty such as Vũ Quỳnh, Phạm Công Trứ and Lê Hi. Today the most popular version of Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư is the "Nội các quan bản" edition which was completed in 1697 with the additional information up to 1656 during the reign of the Emperor Lê Thần Tông and the Lord Trịnh Tráng. Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư is considered the most important and comprehensive historical book about the history of Vietnam from its beginning to the period of the Lê Dynasty.

Contents |

History of compilation

|

During the Fourth Chinese domination, many valuable books of Đại Việt were taken away by the Ming Dynasty including Lê Văn Hưu's Đại Việt sử ký (大越史記, Annals of Đại Việt), the official historical text of the Trần Dynasty and the most comprehensive source of the history of Vietnam up to that period.[1][2][3][4] However, the contents of the Đại Việt sử ký and Lê Văn Hưu's comments about various historical events was fully collected by the historian Phan Phu Tiên in writing the first official annals of the Lê Dynasty after the order of the Emperor Lê Nhân Tông in 1455.[5] The new Đại Việt sử ký of Phan Phu Tiên was supplemented the period from 1223 with the coronation of Trần Thái Tông to 1427 with the retreat of the Ming Dynasty after the victory of Lê Lợi. Phan Phu Tiên's ten-volume work had other names such as Đại Việt sử ký tục biên (大越史記續編序, Supplementary Edition of the Annals of Đại Việt) or Quốc sử biên lục.[5]

During the reign of Lê Thánh Tông, who was an emperor famous for his interest in learning and knowledge, the scholar and historian Ngô Sĩ Liên was appointed to the Bureau of History in 1473.[6] Under the order of Thánh Tông, he based on the works of Lê Văn Hưu and Phan Phu Tiên to write the Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư which was compiled in 15 volumes (quyển) and finished in 1479.[5][7] In compiling the Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư, Ngô Sĩ Liên also drew elements from other books such as Việt điện u linh tập (Compilation of the potent spirits in the Realm of Việt) or Lĩnh Nam chính quái (Extraordinary stories of Lĩnh Nam) which were collections of folk legend and myth but still considered by Ngô Sĩ Liên good sources for history because of their reliable system of citation.[8] This was the first time such sources were used in historiography by a Vietnamese historian.[6] Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư was finally completed in 1479 with the accounts that stopped by the coronation of Lê Thái Tổ in 1428.[6][9] According to Lê Quý Đôn, Ngô Sĩ Liên also compiled an historical text about the reigns of Thái Tổ, Thái Tông and Nhân Tông named Tam triều bản ký (Records of the Three Reigns).

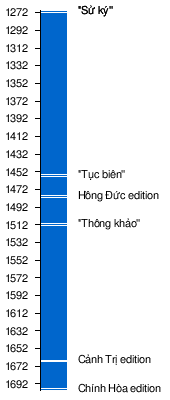

In 1511, the royal historian Vũ Quỳnh reorganized Ngô Sĩ Liên's work in his Việt giám thông khảo by adding the account about Thánh Tông, Hiển Tông, Túc Tông and Uy Mục, which was called Tứ triều bản ký (Records of the Four Reigns).[6][9] Other historians continued to revise Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư and also add the supplemental information about the reign of the Lê Dynasty, notably the 23-volume Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư tục biên (Continued Compilation of the Complete Annals of Đại Việt) was published under the supervision of Phạm Công Trứ in 1665 while the "Nội các quan bản" edition, the most comprehensive and popular version of Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư, was printed in 1697 during the Chính Hòa era by efforts of the historian Lê Hi.[6][10]

Edition

The original 15-volume version of Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư or the Hồng Đức edition (1479), that was named after the era name of Lê Thánh Tông, only existed in form of handwritten manuscript and hence is only partially preserved to this day. The Đại Việt sử ký tục biên or the Cảnh Trị edition (1665), that was the era name of Lê Huyền Tông has a better status of conservation but the most popular and fully preserved version of Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư until now is the Chính Hòa edition (1697) which was the only woodblock printed version of this work.[10] Therefore the Chính Hòa version is considered the most important historical text about the history of Vietnam from its beginning to the period of the Lê Dynasty and has been often reduced, revised and corrected by later historians for contemporary needs.[10][11] Today, a complete set of the "Nội các quan bản" edition is kept in the archives of the École française d'Extrême-Orient in Paris, France. This edition was translated into Vietnamese in 1993 by the Institute of Hán Nôm in Hanoi.[12]

Contents

The format of Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư was modeled after the famous Zizhi Tongjian (資治通鑑, Comprehensive Mirror to Aid in Government) of the Song scholar Sima Guang, which means historical events were redacted in chronological order like annals. Ngô Sĩ Liên separated his book and the history of Vietnam into Ngoại kỷ (Peripheral Records) and Bản kỷ (Basic Records) by the 938 victory of Ngô Quyền in the Battle of Bạch Đằng River.[6] This chronological method of compilation is different from the official historical texts of Chinese dynasties which had the layout divided in biographies of each historical figures, an approach which was initiated by Sima Qian in the Records of the Grand Historian.[13] In record of each Vietnamese emperor, Ngô Sĩ Liên always started with a brief introduction of the emperor which provided an overview about the reigning ruler of the record. In listing the events, the historian sometimes noted an additional story about the historical figure who was mentioned in the event, some had extensive and detailed stories, notably Trần Quốc Tuấn or Trần Thủ Độ. Some important texts were also included in the original form by Ngô Sĩ Liên such as Hịch tướng sĩ or Bình Ngô đại cáo.[13]

| Contents of the Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư (Chính Hòa edition) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peripheral Records (Ngoại kỷ) | ||||

| Volume (Quyển) |

Records (Kỷ) |

Rulers | Period | Note |

| 1 | Hồng Bàng Dynasty | Kinh Dương Vương, Lạc Long Quân, Hùng Vương | [14] | |

| Thục Dynasty | An Dương Vương | 257–208 BCE | [15] | |

| 2 | Triệu Dynasty | Triệu Vũ Đế, Triệu Văn Vương, Triệu Minh Vương, Triệu Ai Vương, Triệu Thuật Dương Vương | 207–111 BCE | [16] |

| 3 | Western Han's domination | 111 BCE–40 | [17] | |

| Queen Trưng | Trưng Sisters | 40–43 | [18] | |

| Eastern Han's domination | 43–186 | [19] | ||

| King Shi | Shi Xie | 186–226 | [20] | |

| 4 | Domination of the Eastern Wu, Jin, Liu Song, Southern Qi, Liang Dynasties | 226–540 | [21] | |

| Early Lý Dynasty | Lý Nam Đế | 544–548 | [22] | |

| Triệu Việt Vương | Triệu Việt Vương | 548–571 | [23] | |

| Later Lý Dynasty | Hậu Lý Nam Đế | 571–602 | [24] | |

| 5 | Domination of the Sui and Tang Dynasties | 602–906 | [25] | |

| North–South separation | 906–938 | [26] | ||

| Ngô Dynasty and 12 Lords Rebellion | Ngô Quyền, Dương Tam Kha, Ngô Xương Văn, Ngô Xương Xí | 938–968 | [27] | |

| Basic Records (Bản kỷ) | ||||

| Volume (Quyển) |

Records (Kỷ) |

Rulers | Period | Note |

| 1 | Đinh Dynasty | Đinh Tiên Hoàng, Đinh Phế Đế | 968–980 | [28] |

| Early Lê Dynasty | Lê Đại Hành, Lê Trung Tông, Lê Ngọa Triều | 980–1009 | [29] | |

| 2 | Lý Dynasty | Lý Thái Tổ, Lý Thái Tông | 1009–1054 | [30] |

| 3 | Lý Dynasty (cont.) | Lý Thánh Tông, Lý Nhân Tông, Lý Thần Tông | 1054–1138 | [31] |

| 4 | Lý Dynasty (cont.) | Lý Anh Tông, Lý Cao Tông, Lý Huệ Tông, Lý Chiêu Hoàng | 1138–1225 | [32] |

| 5 | Trần Dynasty | Trần Thái Tông, Trần Thánh Tông, Trần Nhân Tông | 1225–1293 | [33] |

| 6 | Trần Dynasty (cont.) | Trần Anh Tông, Trần Minh Tông | 1293–1329 | [34] |

| 7 | Trần Dynasty (cont.) | Trần Hiến Tông, Trần Dụ Tông, Trần Nghệ Tông, Trần Duệ Tông | 1329–1377 | [35] |

| 8 | Trần Dynasty (cont.) | Trần Phế Đế, Trần Thuận Tông, Trần Thiếu Đế, Hồ Quý Ly, Hồ Hán Thương | 1377–1407 | [36] |

| 9 | Later Trần Dynasty | Giản Định Đế, Trùng Quang Đế | 1407–1413 | [37] |

| Ming's domination | 1413–1428 | [38] | ||

| 10 | Later Lê Dynasty | Lê Thái Tổ | 1428–1433 | [39] |

| Basic Records, recent compilation (Bản kỷ thực lục) | ||||

| Volume (Quyển) |

Records (Kỷ) |

Rulers | Period | Note |

| 11 | Later Lê Dynasty (cont.) | Lê Thái Tông, Lê Nhân Tông | 1433–1459 | [40] |

| 12 | Later Lê Dynasty (cont.) | Lê Thánh Tông (first record) | 1459–1472 | [41] |

| 13 | Later Lê Dynasty (cont.) | Lê Thánh Tông (second record) | 1472–1497 | [42] |

| 14 | Later Lê Dynasty (cont.) | Lê Hiến Tông, Lê Túc Tông, Lê Uy Mục | 1497–1509 | [43] |

| 15 | Later Lê Dynasty (cont.) | Lê Tương Dực, Lê Chiêu Tông, Lê Cung Hoàng, Mạc Đăng Dung, Mạc Đăng Doanh | 1509–1533 | [44] |

| Basic Records, continued compilation (Bản kỷ tục biên) | ||||

| Volume (Quyển) |

Records (Kỷ) |

Rulers | Period | Note |

| 16 | Later Lê Dynasty (cont.) | Lê Trang Tông, Lê Trung Tông, Lê Anh Tông | 1533–1573 | [45] |

| Mạc clan (supplement) | Mạc Đăng Doanh, Mạc Phúc Hải, Mạc Phúc Nguyên, Mạc Mậu Hợp | |||

| 17 | Later Lê Dynasty (cont.) | Lê Thế Tông | 1573–1599 | [46] |

| Mạc clan (supplement) | Mạc Mậu Hợp | |||

| 18 | Later Lê Dynasty (cont.) | Lê Kính Tông, Lê Chân Tông, Lê Thần Tông | 1599–1662 | [47] |

| 19 | Later Lê Dynasty (cont.) | Lê Huyền Tông, Lê Gia Tông | 1662–1675 | [48] |

Historical perspectives

Comparison with Lê Văn Hưu

While Lê Văn Hưu set the starting point for the history of Vietnam by the foundation of the Kingdom of Nam Việt,[5] Ngô Sĩ Liên took a further step by identifying the mythical and historical figures Kinh Dương Vương and his son Lạc Long Quân as the progenitor of the Vietnamese people.[49] Because of the lack of historical resources about Kinh Dương Vương and Lạc Long Quân, some suggests that Ngô Sĩ Liên's explanation of the Vietnamese people's origin was a measure to extend the longevity of the Vietnamese civilization rather than a literal point of departure.[7][50] From the very beginning of his work, Ngô Sĩ Liên had another difference to Trần scholars in regard to the Hồng Bàng Dynasty, that was while the Trần Dynasty scholars only mentioned the Hồng Bàng Dynasty as a symbol of excellence in the history of Vietnam, Ngô Sĩ Liên defined it the first Vietnamese dynasty which reigned the country from 2879 BC to 258 BC and thus predated the Xia Dynasty, the first dynasty of China, for more than 600 years.[7] However, Ngô Sĩ Liên's account for that long period was so brief[51] that several modern historians challenged the authenticity of his chronology for the Hùng Vương, kings of the Hồng Bàng Dynasty, and speculated that Ngô Sĩ Liên created this specific chronology mainly for the political purpose of the Lê Dynasty.[52]

Like Lê Văn Hưu, Ngô Sĩ Liên treated the Kingdom of Nam Việt as a Vietnamese entity, an opinion which was challenged by several Vietnamese historians from Ngô Thì Sĩ[53] in eighteenth century to modern historians because the kings of Nam Việt were of Chinese origin.[54][55][56]

In their comments on the defeat of Lý Nam Đế by Chen Baxian which led to the Third Chinese domination in Vietnam, Lê Văn Hưu criticized Lý Nam Đế for his lack of ability while Ngô Sĩ Liên remarked that the Will of Heaven was not yet favour with the Vietnamese independence.[57]

Other arguments

Different than Lê Văn Hưu who saved his prior concern for the identity of the country from China,[58] Ngô Sĩ Liên, according to O.W. Wolters, Ngô Sĩ Liên took the Chinese historiography as the standard in assessing historical events of the history of Vietnam.[59] In commenting one event, the historian often cited a passage from Confucianist classics or other Chinese writings such as the Book of Song in order to rhetorically support his own statements.[60]

From his Confucianist point of view, Ngô Sĩ Liên often made negative comments on historical figures who acted against the rule of Confucianism. For example, despite his obvious successful reign, the Emperor Lê Đại Hành was heavily criticized in Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư for his marriage with Dương Vân Nga who was the empress consort of his predecessor. One researcher even speculated that since Ngô Sĩ Liên had a bias against this emperor, he decided to attribute the famous poem Nam quốc sơn hà to Lý Thường Kiệt instead of Lê Đại Hành who was considered by several sources the proper author of the Nam quốc sơn hà.[61][62] Other decisions of the rulers which did not follow the moral and political code of Confucianism were also criticized by Ngô Sĩ Liên such as the coronation of 6 empresses by Đinh Tiên Hoàng, the marriage of Lê Long Đĩnh with 4 empresses or Lý Thái Tổ's lack of interest in Confucianist classics study.[63] Especially in the case of the Trần Dynasty, Ngô Sĩ Liên always made unfavourable remarks on the marriages between closely related members of the Trần clan. The only short period during the reign of the Trần Dynasty that Ngô Sĩ Liên praised was from the death of Trần Thái Tông in 1277 to the death of Trần Anh Tông in 1320 while the historian denounced many actions of the Trần rulers such as the ruthless purge of Trần Thủ Độ against Lý clan or the controversial marriage between Trần Thái Tông and the Princess Thuận Thiên.[64]

Beside its historical value, Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư is also considered an important work of the literature of Vietnam because Ngô Sĩ Liên often provided more information about the mentioned historical figures by the additional stories which were well written like a literary work.[13] From various comments of Ngô Sĩ Liên, it seems that the historian also tried to define and teach moral principles based on the concept of Confucianism.[65] For example, Ngô Sĩ Liên mentioned for several times the definition of a Gentleman (Quân tử) who, according to the historian, had to possess both good qualities and righteous manners, Ngô Sĩ Liên also emphasized the importance of the Gentleman in the dynastic era by pointing out the difference between a Gentleman and a Mean man (Tiểu nhân) or determining what would be the effectiveness of the example of such Gentlemen.[65]

References

Notes

- ^ Trần Trọng Kim 1971, p. 82

- ^ National Bureau for Historical Record 1998, p. 356

- ^ Woodside, Alexander (1988). Vietnam and the Chinese model: a comparative study of Vietnamese and Chinese government in the first half of the nineteenth century. Harvard Univ Asia Center. pp. 125. ISBN 0-674-93721-X.

- ^ Taylor 1991, p. 351

- ^ a b c d "Đại Việt sử ký" (in Vietnamese). Từ điển Bách khoa toàn thư Việt Nam. http://dictionary.bachkhoatoanthu.gov.vn/default.aspx?param=18D9aWQ9MzQyNzAmZ3JvdXBpZD0ma2luZD1zdGFydCZrZXl3b3JkPSVjNCU5MQ==&page=3. Retrieved 2009-12-18.

- ^ a b c d e f Taylor 1991, p. 358

- ^ a b c Pelley 2002, p. 151

- ^ Taylor 1991, pp. 353–355

- ^ a b Keith Weller Taylor & John K. Whitmore 1995, p. 125

- ^ a b c Go Zhen Feng (2002). "Bước đầu tìm hiểu Đại Việt sử ký tục biên" (in Vietnamese). Hán Nôm Magazine (Hanoi: Institute of Hán Nôm) (90). http://www.hannom.org.vn/web/tchn/data/9002_a.htm.

- ^ Boyd, Kelly (1999). Encyclopedia of historians and historical writing, Partie 14, Volume 2. Taylor & Francis. pp. 1265. ISBN 1-884964-33-8.

- ^ Phan Văn Các (1994). "Hán Nôm học trong những năm đầu thời kỳ "Đổi Mới" của đất nước" (in Vietnamese). Hán Nôm Magazine (Hanoi: Institute of Hán Nôm) (94). http://www.hannom.org.vn/web/tchn/data/9404v.htm.

- ^ a b c Hoàng Văn Lâu (2003). "Lối viết "truyện" trong bộ sử biên niên Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư" (in Vietnamese). Hán Nôm Magazine (Hanoi: Institute of Hán Nôm) (99). http://www.hannom.org.vn/web/tchn/data/9903_a.htm.

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, pp. 3–6

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, pp. 6–9

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, pp. 10–19

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, p. 20

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, p. 21

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, pp. 21–24

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, pp. 25–27

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, pp. 28–36

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, pp. 36–38

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, pp. 38–39

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, pp. 39–41

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, pp. 42–51

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, pp. 51–53

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, pp. 53–57

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, pp. 58–65

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, pp. 65–79

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, pp. 80–104

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, pp. 105–134

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, pp. 135–158

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, pp. 159–204

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, pp. 205–239

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, pp. 240–271

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, pp. 272–308

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, pp. 309–322

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, pp. 322–324

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, pp. 325–372

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, pp. 373–428

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, pp. 428–477

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, pp. 478–522

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, pp. 523–552

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, pp. 553–596

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, pp. 597–618

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, pp. 619–655

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, pp. 656–687

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, pp. 688–738

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, pp. 3–4

- ^ Pelley 2002, p. 65

- ^ Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, pp. 4–6

- ^ Pelley 2002, pp. 151–152

- ^ Ngô Thì Sĩ (1991) (in Vietnamese). Việt sử tiêu án. History & Literature Publishing House. pp. 8.

- ^ "Nam Việt" (in Vietnamese). Từ điển Bách khoa toàn thư Việt Nam. http://dictionary.bachkhoatoanthu.gov.vn/default.aspx?param=1A21aWQ9MjExNzQmZ3JvdXBpZD0ma2luZD0ma2V5d29yZD1OYW0rVmklZTElYmIlODd0&page=1. Retrieved 2009-12-18.

- ^ "Triệu Đà" (in Vietnamese). Từ điển Bách khoa toàn thư Việt Nam. http://dictionary.bachkhoatoanthu.gov.vn/default.aspx?param=1E6EaWQ9MjA4NSZncm91cGlkPSZraW5kPSZrZXl3b3JkPVRyaSVlMSViYiU4N3UrJWM0JTkwJWMzJWEw&page=1. Retrieved 2009-12-18.

- ^ Phan Huy Lê, Dương Thị The, Nguyễn Thị Thoa (2001). "Vài nét về bộ sử của Vương triều Tây Sơn" (in Vietnamese). Hán Nôm Magazine (Hanoi: Institute of Hán Nôm) (85). http://www.hannom.org.vn/web/tchn/data/8501v.htm.

- ^ Taylor 1991, p. 144

- ^ Womack, Brantly (2006). China and Vietnam: the politics of asymmetry. Cambridge University Press. pp. 119. ISBN 0-521-61834-7.

- ^ Anthony Reid, Kristine Alilunas-Rodgers 2001, p. 94

- ^ Anthony Reid, Kristine Alilunas-Rodgers 2001, p. 95

- ^ Bùi Duy Tân (2005). "Nam quốc sơn hà và Quốc tộ - Hai kiệt tác văn chương chữ Hán ngang qua triều đại Lê Hoàn" (in Vietnamese). Hán Nôm Magazine (Hanoi: Institute of Hán Nôm) (05). http://www.hannom.org.vn/web/tchn/data/0505_a.htm.

- ^ Nguyễn Thị Oanh (2001). "Về thời điểm ra đời của bài thơ Nam quốc sơn hà" (in Vietnamese). Hán Nôm Magazine (Hanoi: Institute of Hán Nôm) (02). http://www.hannom.org.vn/web/tchn/data/0201_a.htm.

- ^ Phạm Văn Khoái, Tạ Doãn Quyết (2001). "Hán văn Lý-Trần và Hán văn thời Nguyễn trong cái nhìn vận động của cấu trúc văn hóa Việt Nam thời trung đại" (in Vietnamese). Hán Nôm Magazine (Hanoi: Institute of Hán Nôm) (03). http://www.hannom.org.vn/web/tchn/data/0301_a.htm.

- ^ Anthony Reid, Kristine Alilunas-Rodgers 2001, pp. 94–98

- ^ a b Anthony Reid, Kristine Alilunas-Rodgers 2001, pp. 99–100

Bibliography

- National Bureau for Historical Record (1998) (in Vietnamese), Khâm định Việt sử Thông giám cương mục, Hanoi: Education Publishing House

- Chapuis, Oscar (1995), A history of Vietnam: from Hong Bang to Tu Duc, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 0-313-29622-7, http://books.google.com/books?id=Jskyi00bspcC&lpg=PA85&dq=%22tran%20anh%20tong%22&as_brr=3&hl=fr&pg=PA85#v=onepage&q=%22tran%20anh%20tong%22&f=false

- Ngô Sĩ Liên (1993) (in Vietnamese), Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư (Nội các quan bản ed.), Hanoi: Social Science Publishing House

- Pelley, Patricia M. (2002), Postcolonial Vietnam: new histories of the national past, Duke University Press, ISBN 0-8223-2966-2

- Tuyet Nhung Tran, Anthony J. S. Reid (2006), Việt Nam Borderless Histories, Madison, Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press, ISBN 978-0-299-21770-9

- Anthony Reid, Kristine Alilunas-Rodgers (2001), Sojourners and settlers: histories of Southeast Asia and the Chinese, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 0-8248-2446-6

- Keith Weller Taylor & John K. Whitmore (1995), Essays into Vietnamese pasts, Volume 19, SEAP Publications, ISBN 0-87727-718-4

- Trần Trọng Kim (1971) (in Vietnamese), Việt Nam sử lược, Saigon: Center for School Materials

- Tuyet Nhung Tran, Anthony J. S. Reid (2006), Việt Nam Borderless Histories, Madison, Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press, ISBN 978-0-299-21770-9

External links

- "Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư (original Chinese text)" (in Hán tự) (Nội các quan bản (1697) ed.). nomna.org. http://www.nomna.org/DVSKTT/dvsktt.php.

- "Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư (Vietnamese translation)" (in Vietnamese) (Nội các quan bản (1697) ed.). Vietnamese Academy of Social Sciences. http://www.informatik.uni-leipzig.de/~duc/sach/dvsktt/.